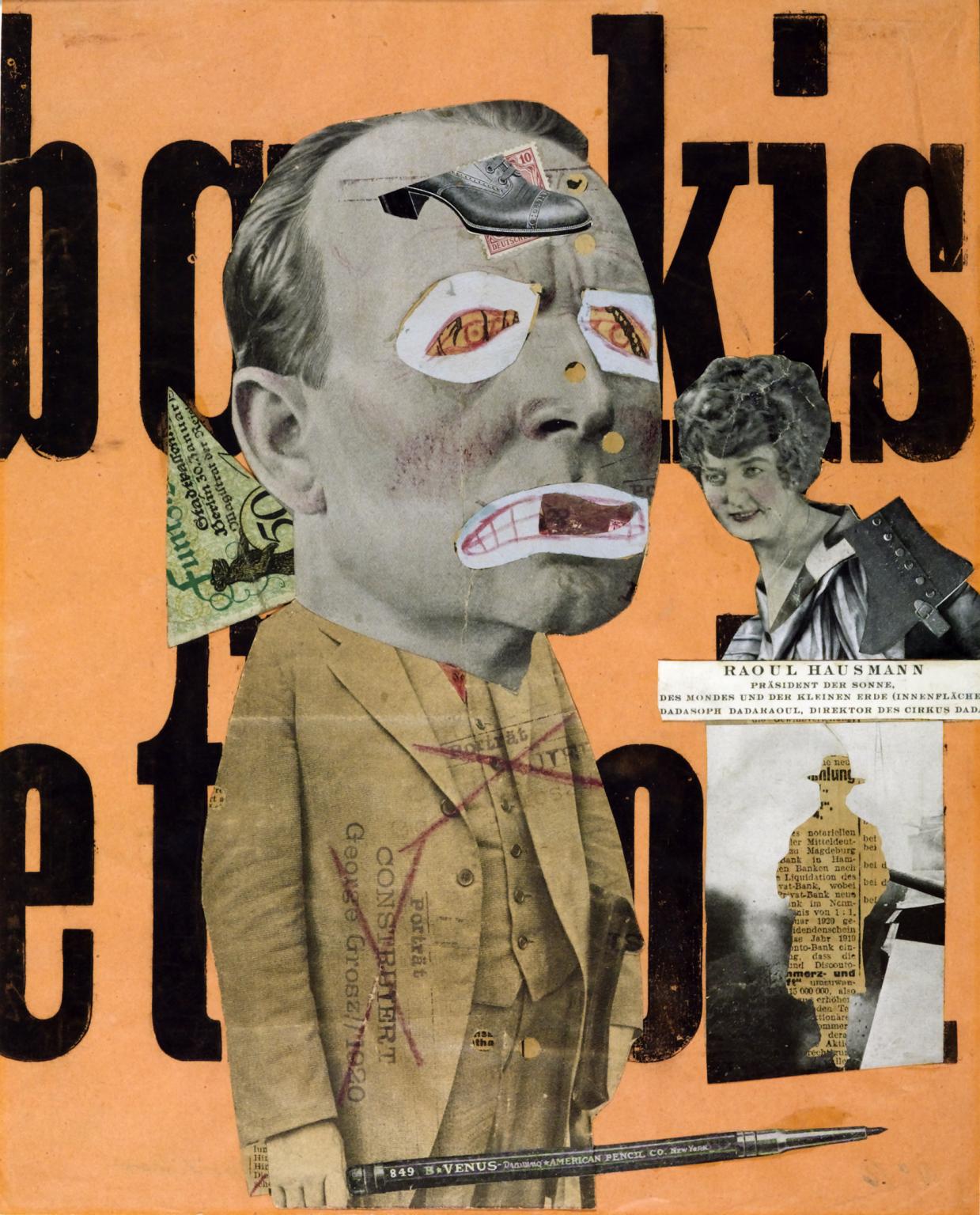

The Art Critic 1919-20 Raoul Hausmann 1886-1971 Purchased 1974 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T01918

T A T E – Definition

“Dada was an art movement formed during the First World War in Zurich in negative reaction to the horrors and folly of the war. The art, poetry and performance produced by dada artists is often satirical and nonsensical in nature” – https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/d/dada

Vaporwave is a millennial art movement that seeks to convey the angst’s and joys of the “Internet Generation” by appropriating old tropes to create new statements and speculations on millennial life. It’s inextricably tied to the past — more specifically to the ’80s and ’90s, decades that saw the emergence of the information age as a part of everyday life. The advent of personal computing made the world smaller than ever before, and a technological boom courtesy of Japanese tech companies saw the aesthetic fixations of American society shift away from the lava lamps and shag carpets of the ’70s to a decade that was all about the future. A far cry from the sleek, all-American retro-futurist stylings of the 1950s, the future of the 1980s was all about neon pinks, Japanese characters and aviator sunglasses. By this time, many of these aesthetic concepts had already begun to manifest themselves in films like “Blade Runner,” and later “Ghost in the Shell.” Deemed “Cyberpunk,” this type of art would come to exemplify the speculations and musings of a society on the cusp of an information explosion.

Fast-forward to the 2010s, and the children of this era have now grown up and are creating art of their own. The Information Age has not only made the world more connected, but it has made companies more connected to consumers. Marketing has become less about what the consumer thinks and more about what they feel. The early days of this trend would serve as the artistic muse for the Vaporwave movement, which seeks to expose the complicated and often contradictory relationships that millennials share with the internet age. The images associated with Vaporwave — from the pixelated look of the early-internet to the generic sounds of elevator music — all share one thing in common. They evoke a sense of the uncanny valley, or the unsettling effect of seeing something almost human, but not quite. While it typically refers to robots, animations and other would-be-humans, it applies to many Vaporwave tropes. These artifacts are products of a time when companies sought to make their consumers feel very specific ways.

It’s by exposing this chink in our understanding of pop culture that Vaporwave manages to make us feel both at ease and on edge, simultaneously filled with nostalgia and angst. It is at once about our past and our future. As Vaporwave matured and developed, it began to grow further into the realms of science fiction, speculative fiction and surrealism. Vaporwave artists were fascinated by just how powerfully evocative these artifacts could be. The movement exposed deeper questions about the effects of digitization on our society: Why does the soft glow of neon make you feel wistful? What about a crackling record or a Coca-Cola jingle evokes such strong feelings when placed in the right context? Why can a computer glitch feel gut-wrenching?

For an artistic movement that’s so fixated on the passage of time and the creation of new from the old, it should come as no surprise that Vaporwave is in fact the reincarnation of a much older idea. I speak, of course, of Dada, the avant-garde art movement that brought forth artists like Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp and Otto Dix. The gathering of Dada artists in New York’s Cabaret Voltaire would birth some of the Lost Generation’s most identifiable visual motifs. Deemed “anti-art,” the goal of Dada was to expose the consumerist values of post-war society and convey them through re-purposing the ordinary and familiar into the bizarre and unsettling. If the ideological core of Vaporwave now sounds familiar, that’s because it is. Both movements were brought about by critical minds observing the society in which they lived, both are viciously anti-consumerist, and both serve as a cultural snapshot of a generation.

While it may be jumping the gun to assign the same level of cultural significance to Vaporwave as one would to Dada, the ideological and conceptual similarities between the two movements are striking. Vaporwave’s circulation as an internet meme adds an entirely new facet to the discussion, as the cultural clout of memes in the context of the arts has yet to be formally established. While it may be tempting to dismiss the significance of memes due to their often ridiculous nature, one could also view the medium as a unique form of sharing ideas, one that no prior generation has used. Only time will tell where Vaporwave lands in our cultural lexicon, but until then artists like Vektroid will keep on cruising down the sonic highways of yesteryear.